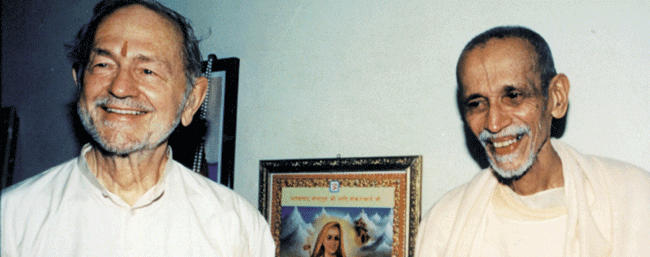

In 1995, Swamiji visited Swami Chidananda in Rishikesh, India. They had met more than forty years before, when both were young monks. Chidananda is one of the best-known disciples of the great yogi, Swami Sivananda. He is also president of the Divine Life Society, one of the largest spiritual societies in India and one of the most well respected in the world.

In 1995, Swamiji visited Swami Chidananda in Rishikesh, India. They had met more than forty years before, when both were young monks. Chidananda is one of the best-known disciples of the great yogi, Swami Sivananda. He is also president of the Divine Life Society, one of the largest spiritual societies in India and one of the most well respected in the world.

There is much that is similar in the lives of these two swamis, one Indian, one American. Both became disciples and monks at a young age. To each has fallen the lion’s share of responsibility for carrying on his guru’s work. Both lead international organizations and are known and revered by thousands of people around the world.

Swamiji describes Chidananda as “The monk I respect most in all of India.” The two met occasionally over the years, but not often, and were seeing each other now after a long separation. They greeted each other with folded hands and a long calm look into one another’s eyes. They sat down together on cushions placed on the floor with a group of devotees crowded in a semi-circle around them.

Swamiji spoke first. “And how is the Divine Life Society?” he asked Chidananda.

With an amused half smile, Chidananda said, “Fine,” as if he were commenting on the comfort of his cushion, rather than the state of his life’s work.

Then, with a twinkle in his eye, as if to say, “I’ve caught the ball and now I’ll toss it back,” Chidananda asked Swamiji, “And how is Ananda?”

In perfect imitation of Chidananda’s response, Swamiji said, “Fine.”

Then both swamis began to chuckle, and the chuckle grew into soft, musical laughter.

Suddenly I “got the joke,” and felt a rising joy from my heart to my spiritual eye. The swamis had come to a perfect understanding. Your “life’s work” ? My “life’s work” ? What does it matter?

What was delightful in them was not so much what each had accomplished, but what each had become.

From Swami Kriyananda As We Have Known Him by Asha Praver

The greatness of a spiritual teacher is only partially revealed by the work of his own hands. The rest of the story is one he cannot tell for himself, the influence of his consciousness on those who come in contact with him.

In some two hundred stories spanning more than forty years, personal reminiscences and private moments with this beloved teacher become universal life lessons for us all.